Categories:

【Lewis Revill】Implementing Machine Code Optimizations for RISC-V in LLVM

by Lewis Revill

Implementing Machine Code Optimizations for RISC-V in LLVM — A Detailed Look - by Lewis Revill

This blog post describes three optimizations — shrink wrapping, save/restore & machine outlining — which I have been working on for the RISC-V backend in LLVM. These optimizations focus on transforming a machine code representation of a program in order to improve performance or decrease the total size of the program.

Background

Forming the final part of the compilation process, a program is translated into its machine code representation before being converted into its final form — IE an executable, object file or assembly file. This stage is realistically the last chance for the compiler to perform optimizations on the program, and while the higher level information about semantics and control flow has been lost, one advantage of performing optimizations at this stage is precisely the fact that there are no more stages to the pipeline; we can rely on heuristics that we determine about the program being much more accurate.

Basic blocks, prologues and epilogues

The most fundamental unit of the machine code representation is the machine code instruction.

Basic blocks are sets of these instructions, which can be considered the building blocks of control flow within the program. For example, the body of an if statement will usually end up as a basic block. These basic blocks can be given a label if they are needed as a target to jump to, and can either end by falling through to the next block, or with branch and/or jump instructions.

The following shows an example of some basic blocks as represented in assembly — note the use of left-justified labels and comments to denote a basic block:

# %bb.0:

mv s0, a0

beqz a1, .LBB0_2

# conditionally fall through

# %bb.1:

addi a0, s0, -1

addi a1, zero, 1

call foo

add a0, a0, s0

j .LBB0_5

.LBB0_2:

bgtz s0, .LBB0_4

# conditionally fall through

# %bb.3:

mv s0, zero

# fall through

.LBB0_4:

addi a2, s0, -1

mv a0, s0

mv a1, zero

mv a3, zero

call __muldi3

slli a1, a1, 31

srli a0, a0, 1

or a0, a0, a1

# fall through

.LBB0_5:

ret

A function will be constructed from a collection of basic blocks, with at least one basic block terminating with a return instruction (except in the rare case that control flow never needs to leave the function).

A function will usually contain code to setup and destroy the frame in the ‘prologue’ and ‘epilogue’ respectively. The frame is the word used to describe the section of the stack used by the current function, and the purpose of the prologue/epilogue code is to manage the use of the frame. This involves adjusting the stack pointer such that it points to a valid location in the frame; adjusting the frame pointer when it is needed such that it references the unchanging location of the frame itself; and saving and restoring state of registers which the caller of the function assumes will be preserved.

The following is an example of prologue/epilogue code in assembly — this simply saves and restores the state of some registers on the stack.

# %bb.0:

addi sp, sp, -16

sw ra, 12(sp)

sw s0, 8(sp)

# Code which uses ra & s0...

# ...

lw s0, 8(sp)

lw ra 12(sp)

addi sp, sp, 16

ret

Implementing the optimizations in LLVM

LLVM is designed to be a compiler infrastructure, allowing different ‘backends’ — or ‘targets’ — to utilize common functionality in order to compile code for their architecture. This includes algorithms to transform machine code. Because of this, in my implementation of these three optimizations for RISC-V I was able to reduce the amount of changes needed, as a lot of the time I was simply implementing hooks for the generic algorithms to use to find out more about the specific requirements for RISC-V. This was not the case for the save/restore optimization but there still existed hooks that allowed me to be able to insert my own logic in the correct way.

Shrink wrapping

Shrink wrapping is an optimization which rearranges the prologue and epilogue code within the function such that it covers the smallest possible range. For example, if a function only made use of preserved registers within the true condition of a branch, then running the prologue/epilogue code on function entry and exit is unnecessary; it is only needed on the entry and exit of the blocks contained within that true condition.

Prior to my patches, if the shrink wrapping optimization was enabled in RISC-V it would cause an assertion failure when the prologue was emitted, due to the following line:

assert(&MF.front() == &MBB && "Shrink-wrapping not yet supported");

In other words, the assertion triggers if we attempt to insert the prologue in any basic block other than the very first block in the function, which is exactly what the shrink wrapping optimization attempts to do. So my approach was simply to delete this line, and see what other code needed to be changed to get this to work correctly.

The changes that were required were simply to update the logic which determined the insertion point of the epilogue; previously this logic decided that the epilogue would be inserted exactly one instruction before the last instruction in the block, since it could assume the block ends with a return instruction (IE: a terminator). I modified this logic to properly account for situations where this is not the case:

// If this is not a terminator, the actual insert location should be after the

// last instruction.

if (!MBBI->isTerminator())

MBBI = std::next(MBBI);

More complex logic was needed once save/restore was implemented, since this complicated the requirements for being able to insert prologue and epilogue code in a given location. Most importantly, we could not move the epilogue, since the routines used for save/restore use a ‘tail return’. A tail return assumes that the function calling it has no more code that needs to be run, so instead of returning control to that function, it returns to the function which called that function instead.

The full implementation of shrink wrapping for RISC-V can be found on Phabricator. Currently this can be enabled by passing -mllvm -enable-shrink-wrap to the Clang compiler.

Save/restore

Save/restore is the colloquial name for an optimization which replaces the save and restore code in prologues and epilogues with calls to assembly routines. This reduces the code size of each function, and the idea is that, in a large enough program, the overall reduction in code size will outweigh the one-time cost of including the assembly routines.

There is no ‘pre-packed’ logic in LLVM for emitting calls to assembly routines in prologues and epilogues, but we need to make sure that LLVM knows that we know how to handle the reserved registers ourselves, so they don’t need stack locations to be calculated for them:

// Frame indexes representing locations of CSRs which are given a fixed location

// by save/restore libcalls.

static std::map<unsigned, int> FixedCSRFIMap = {

{/*ra*/ RISCV::X1, -1},

{/*s0*/ RISCV::X8, -2},

{/*s1*/ RISCV::X9, -3},

{/*s2*/ RISCV::X18, -4},

{/*s3*/ RISCV::X19, -5},

{/*s4*/ RISCV::X20, -6},

{/*s5*/ RISCV::X21, -7},

{/*s6*/ RISCV::X22, -8},

{/*s7*/ RISCV::X23, -9},

{/*s8*/ RISCV::X24, -10},

{/*s9*/ RISCV::X25, -11},

{/*s10*/ RISCV::X26, -12},

{/*s11*/ RISCV::X27, -13}};

bool RISCVRegisterInfo::hasReservedSpillSlot(const MachineFunction &MF,

unsigned Reg,

int &FrameIdx) const {

const auto *RVFI = MF.getInfo<RISCVMachineFunctionInfo>();

if (!RVFI->useSaveRestoreLibCalls())

return false;

auto FII = FixedCSRFIMap.find(Reg);

if (FII == FixedCSRFIMap.end())

return false;

FrameIdx = FII->second;

return true;

}

A slight difficulty with using an assembly routine for saving registers is that we haven’t yet saved the state of the return address register, so we can’t actually use it for the call to the routine itself. The workaround is to use a different register as a temporary return address register:

// Add spill libcall via non-callee-saved register t0.

BuildMI(MBB, MI, DL, TII.get(RISCV::PseudoCALLReg), RISCV::X5)

.addExternalSymbol(SpillLibCall, RISCVII::MO_CALL)

.setMIFlag(MachineInstr::FrameSetup);

The full implementation of save/restore for RISC-V can be found on Phabricator. Currently this can be enabled by passing -msave-restore to the Clang compiler.

Machine outlining

Machine outlining is a more general approach to optimizing the size of machine code, where — in a similar manner to save/restore — common code sequences throughout a program are extracted into functions, and the original copies are replaced with calls to that function.

Machine outlining is another optimization that is already available in LLVM for targets to utilize. The algorithm can be described as follows:

- Map each machine code instruction to a number, unique to the exact behaviour of that instruction. Construct a ‘string’ representing the entire program from these.

- Transform this into a suffix tree — a data structure representing a string as a set of common substrings with different suffixes.

- Repeatedly query the suffix tree for the next outlining candidate — the longest non-leaf substring with more than one occurence — and replace each occurence with a call to an outlined function.

For more detail , Jessica Paquette’s talk at the 2016 LLVM developers’ meeting gives a fantastic overview of the machine outliner:

For the target implementation, we need to define some hooks to tell the algorithm when it is safe to outline code. For RISC-V this involves checking that outlining wouldn’t override expected linker behaviour:

bool RISCVInstrInfo::isFunctionSafeToOutlineFrom(

MachineFunction &MF, bool OutlineFromLinkOnceODRs) const {

const Function &F = MF.getFunction();

// Can F be deduplicated by the linker? If it can, don't outline from it.

if (!OutlineFromLinkOnceODRs && F.hasLinkOnceODRLinkage())

return false;

// Don't outline from functions with section markings; the program could

// expect that all the code is in the named section.

if (F.hasSection())

return false;

// It's safe to outline from MF.

return true;

}

After the machine outliner has produced outlining candidates, the target can provide information about the candidate sequence and the locations in which it occurs. For RISC-V we also use this opportunity to ensure that we are able to insert a call to an outlined function using the same temporary return address register as the save/restore implementation uses:

// First we need to filter out candidates where the X5 register (IE t0) can't

// be used to setup the function call.

auto CantInsertCall = [](outliner::Candidate &C) {

const TargetRegisterInfo *TRI = C.getMF()->getSubtarget().getRegisterInfo();

C.initLRU(*TRI);

LiveRegUnits LRU = C.LRU;

return !LRU.available(RISCV::X5);

};

RepeatedSequenceLocs.erase(std::remove_if(RepeatedSequenceLocs.begin(),

RepeatedSequenceLocs.end(),

CantInsertCall),

RepeatedSequenceLocs.end());

Finally, the outlined function is constructed and the required calls to the outlined function are inserted in place of the original sequences. The target has the opportunity to perform any modifications on the outlined function, and must insert the calls to the function. For RISC-V, we use the same method of calling the outlined function as the save/restore implementation uses to call the assembly routines.

The full implementation of machine outlining for RISC-V can be found on Phabricator. Currently this can be enabled by passing -mllvm -enable-machine-outliner to the Clang compiler.

Results

The Embench benchmark suite

The Embench benchmark suite is a set of benchmarks intended to produce fair and easily comparable measurements for evaluating performance on embedded systems. To evaluate the effectiveness of these three machine code optimizations I used Embench to produce size and speed measurements for various configurations.

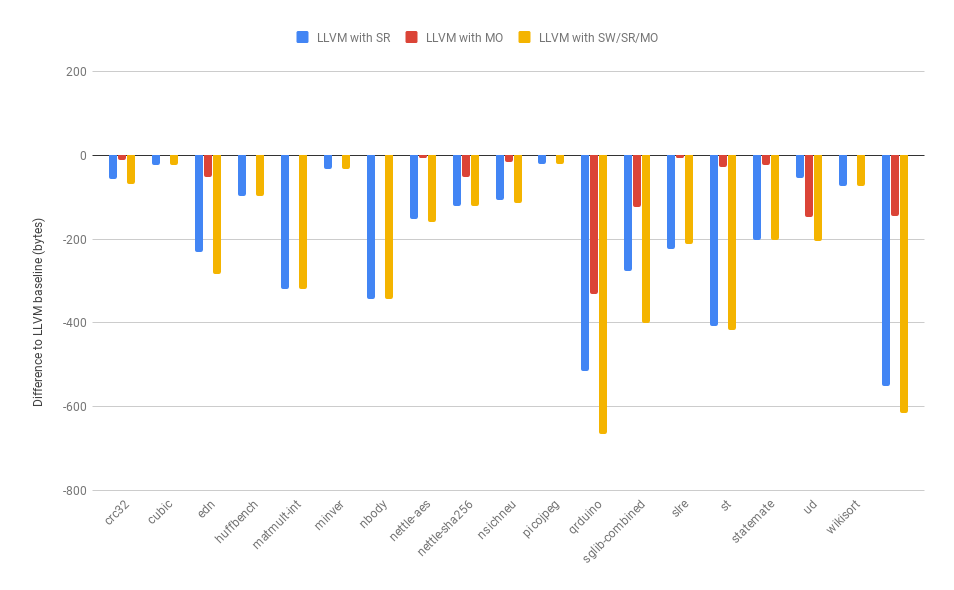

Size measurements — dummy libraries

Compiling the benchmark programs with dummy libraries linked instead of the real libraries reduces the impact of the size of the libraries on the absolute code size measurements. In our case this would theoretically make it easier to see small differences between each configuration.

It’s worth noting that I removed the data for the shrink wrapping optimization for the size measurements, since it has no impact on code size. This is not unexpected — despite its name — since the optimization is just moving code around. I have also chosen to report the absolute sizes; Embench by default reports measurements relative to a standard setup to keep the results in context, however for our purposes we are comparing directly to our own baseline — LLVM without our optimizations — so comparing absolute sizes is more appropriate.

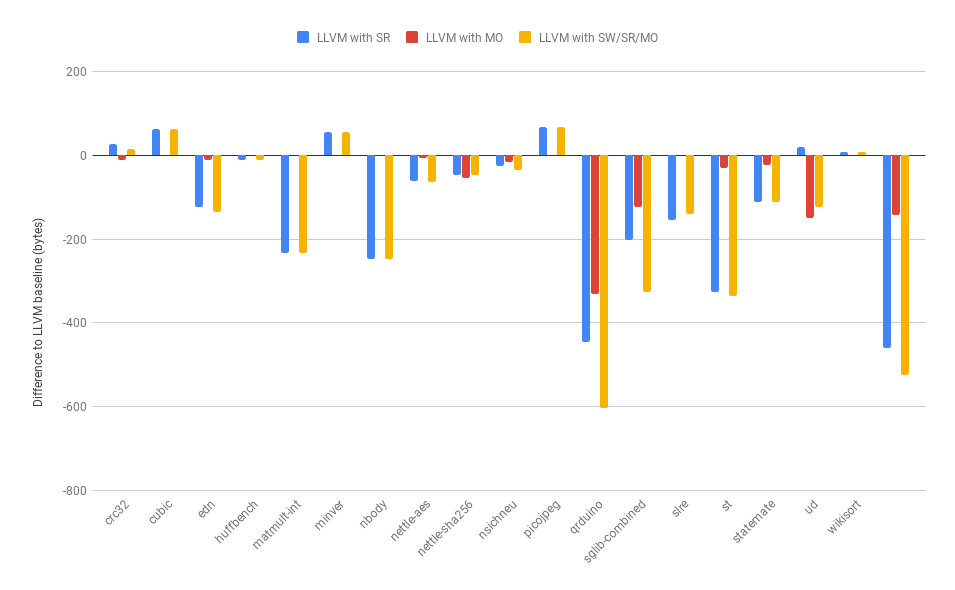

Size measurements — real libraries

In this case, each of the configurations are being linked against real libraries. This actually helps us to present a more accurate comparison between the optimizations, since the save/restore optimization requires linking in a small amount of additional library code — the assembly routines — and it can be seen that in a few cases this does outweigh the initial decrease in code size.

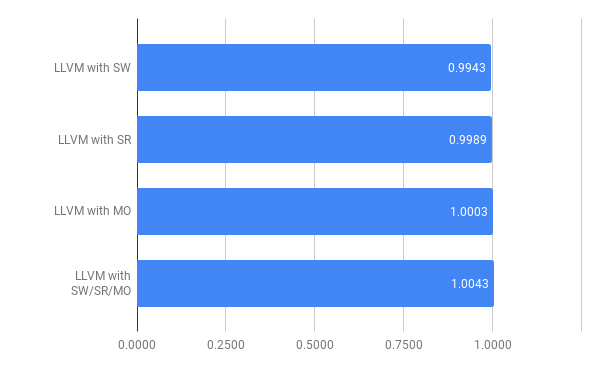

Speed measurements

Here the geometric mean of the relative performance is shown.

Since two of the three optimizations are focussed on size, it wasn’t as relevant to investigate the speed results as much. However it’s important to show that performance relative to the standard setup remains reasonable. One interesting thing to note here was that on these benchmarks shrink wrapping did not have much of an effect, indicating that the optimization is only expected to make a marginal difference, or even that the type of programs used didn’t present much opportunities for the optimization to have an effect.

Conclusion

Using the existing infrastructure in LLVM, I was able to implement a set of optimizations which transform RISC-V machine code — shrink wrapping, save restore & machine outlining. The results showed that save restore and machine outlining gave a significant improvement in code size, whereas while shrink wrapping did not give an improvement in speed, we expect that for other benchmarks there are likely some areas where this optimization will be effective.

Currently work-in-progress implementations are available on Phabricator, and a constantly updated branch exists on Embecosm’s LLVM fork, where you can use the experimental flags described above to experiment with the optimizations.